A Reflection on the Intersection of the Queer Community With the Climate Justice Movement.

Very often, when you attend protests these days, especially those focused on social justice or the environment, you’ll notice a strong presence of the queer community. In fact, research in the U.S. show that LGBTQ+ individuals tend to place a high value on politicians’ approaches to climate and environmental issues. Even in my own life, the most passionate activists I’ve known have been loud and proud members of the LGBTQ+ community.

So when Pride Month began, I found myself curious about the queer presence in our own office. What had brought my colleagues to the field of forest restoration and youth empowerment? Did their queer identities intersect with their work at Plant-for-the-Planet in any meaningful way? And as a new employee, I couldn’t help but wonder: is there even a queer scene here and how visible is it? This is an account of my conversations with three employees and one youth ambassador of Plant-for-the-Planet.

Most of us, if not overtaken by a consuming love for nature, start being climate justice advocates for the sake of social justice. That social starting point is often deeply personal. One colleague described how their activism began at a homeless shelter by simply listening to people’s stories, witnessing inequality in its rawest form. “Once you start seeing it there,” they told me, “you start seeing inequalities everywhere.” Climate injustice, they realized, is just another expression of that same system. Their journey, like the journey of many others at Plant-for-the-Planet, didn’t start with trees, but with people.

This broader view of climate activism is deeply rooted in the idea of intersectionality. The work we do in forest restoration goes beyond planting trees, it includes youth empowerment, education, and supporting women in Ghana through economic opportunities that are brought about through forest restoration. For some, especially those who are queer, this approach feels both practical and deeply personal. “You can’t separate climate from other justice work,” one of my other colleagues said. “When we empower women or stand with queer youth, that’s climate work too because it’s all about who gets to survive.”

And survival is a key word here. Another colleague, reflecting on their own path, talked about a kind of existential exhaustion, what they called Weltschmerz, a German term loosely translated as “world pain.” It’s that heavy, suffocating feeling that comes from seeing the world’s inequalities pile up: the rich getting richer, nature being destroyed, people being left behind. For them, this pain became a turning point. It didn’t paralyze them. It pushed them to act.

One thing became very clear in these conversations: being queer often means being attuned to systems of power and exclusion. It means learning early on how to navigate crisis. As one colleague put it, “We have this joke in the queer community: we’re used to crisis.” That readiness, that resilience, is exactly what the climate movement needs. Because the climate crisis isn’t just environmental, it’s systemic. It threatens those already on the margins: LGBTQ+ folks, Indigenous peoples, people in the Global South. The ones who’ve contributed the least to the crisis are the ones suffering the most.

And so the intersection isn’t accidental. It’s born out of necessity and shared struggle. One person reflected that their queer identity actually deepened their empathy when working on climate projects: “I know how it feels to be discriminated against,” they said. “So when I work on climate, I always ask: how do the people living there feel?” That question is so basic, yet so often missing from big climate strategies, is a reminder that climate justice is, fundamentally, human rights work.

There’s also something deeply emotional and affirming in finding visibility in a workplace. “At Plant-for-the-Planet,” one employee shared, “I feel like I don’t have to quiet any part of myself. That’s rare.” In corporate environments, they had often felt hollowed out, unable to bring their full self to the table. But here, in a movement built on justice, they finally found calibration between who they are and what they do.

Visibility, it turns out, isn’t just symbolic, it’s strategic. One employee described their first protest as a Pride march, and how that energy through the chanting, the laughter, the shared urgency had felt strikingly similar at later climate protests. “We’re all fighting for our lives here,” they said. It’s hard to describe that feeling unless you’ve been there: the sense that you are part of something much bigger than yourself. Pride and protest alike have taught us that joy is resistance. Whether it’s bringing rainbow glitter to a climate march or dancing after a difficult campaign win, celebration is part of the fight.

Still, we can’t ignore how easily movements fail when they overlook the people who built them. “The most marginalized voices, trans women of color, Indigenous leaders, they’ve always been doing this work,” one person reminded me. “But the movement isn’t truly intersectional until they’re at every decision-making table.” It’s a fair critique of performative activism. A rainbow logo in June doesn’t mean much if you’re not funding queer organizers in the Global South the other eleven months of the year.

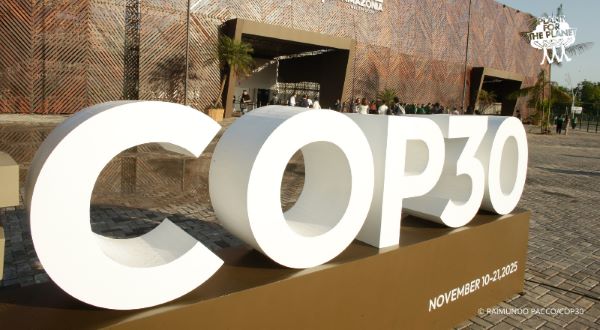

In the same vein, representation isn’t something we should ration. “There’s no such thing as ‘too much’ representation,” one person said. “We keep fighting until the world reflects all of us.” That includes language, policies, and leadership. As someone else put it, “Until I see trans people leading at COP, not just rainbow logos, we’re just decorating the same broken system.”

And that’s the danger. When we ignore each other’s struggles or tokenize participation, we fracture the movement. Progress slows. The work gets harder. Because climate change isn’t a singular crisis, it’s a web of injustices, and you can’t untangle one thread without pulling on the rest. Queer folks know this. Indigenous land defenders know this. So do disabled youth, rural organizers, and immigrant workers. The lesson is clear: we either move together, or we don’t move at all.

I’ve thought a lot about what hope means after these conversations. One person told me that finding the queer community was like discovering a missing piece of themselves. That feeling of showing up fully and of finally being seen is what they now seek to recreate in the climate movement. For another, it’s the friends who bring sequins and sass to every protest that keep them going. “We’re not just fighting against collapse,” they said. “We’re fighting for the right to celebrate our survival.”

What touched me the most, when talking to a youth ambassador, was how excited they were to find out that Plant-for-the-Planet (aka this author) was curious about the intersection of the climate movement and LGBTQ+ rights. Their excitement was contagious, I quite literally could not not smile during our interview.

Because in the end, creating a world resilient to climate change, one that’s truly safe for all, requires more than carbon targets or new tech. It demands spaces where everyone can be heard, where no one has to hide, and where our identities are not just accepted but celebrated as part of the fight. That is the vision of climate justice that many queer activists are already living. One protest, one reforested plot, one shimmering, sweaty Pride march at a time.