Since COP 28, the idea of a global investment fund for tropical rainforest protection has taken shape. Over time, the concept has developed and evolved into the Tropical Forest Forever Facility (TFFF). The proposed global, permanent fund is designed to support the long-term conservation of tropical forests. Spearheaded by the Government of Brazil, in dialogue with 11 other countries, the initiative is scheduled to be formally launched at COP 30 in Belém, Brazil.

Unlike traditional conservation finance efforts that often rely on new donor pledges, the TFFF proposes an innovative approach – mobilizing investments from governments, sovereign wealth funds and institutional investors to create a long-term investment facility that generates annual payments for forest conservation.

Plant-for-the-Planet launched TFFF Watch – The Platform for Transparency and Investment Tracking

Investments are still needed, as the TFFF requires $25 billion in sponsor capital from governments and $100 billion in private investments. With the announcement by Brazilian President Lula da Silva that Brazil will be the first country to invest $1 billion into the $125 billion fund, an important signal has been sent. To explore the TFFF’s potential and track investments made into the fund, Plant-for-the-Planet has launched a new platform: tfffwatch.org.

Based on satellite data, it provides country-specific estimates of how much funding each rainforest country should receive. Once the TFFF becomes operational, the platform will track future developments and monitor the fund’s impact. Initial results from the analysis show that countries benefit significantly when they halt deforestation.

How the TFFF works: Conservation Rewarded, Deforestation Penalized

What sets the TFFF apart from other forest protection programs is its innovative financing model. By investing funds provided by governments and private investors, the TFFF aims to generate stable, long-term revenue.

Countries receive $4 per hectare of preserved forest, but only if:

- The average deforestation rate over the last three years is below 0.5%

- The degradation rate decreases in the year they join the TFFF

Deforestation and degradation will be penalized by the fund through deductions from the payments:

- $400 per hectare deforested under a total rate of 0.3%

- $800 per hectare deforested above a total rate of 0.3%

- $140 per hectare degraded through wildfire

Additionally, at least 20% of a country’s payout must be allocated to Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities (IPLCs).

How much money will countries get from the TFFF?

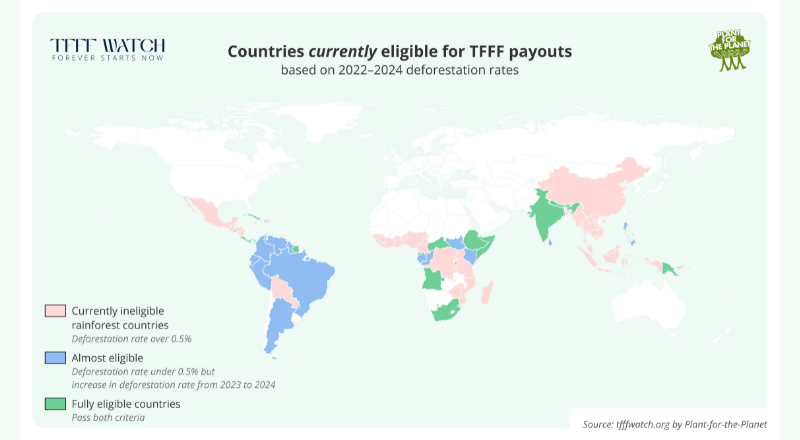

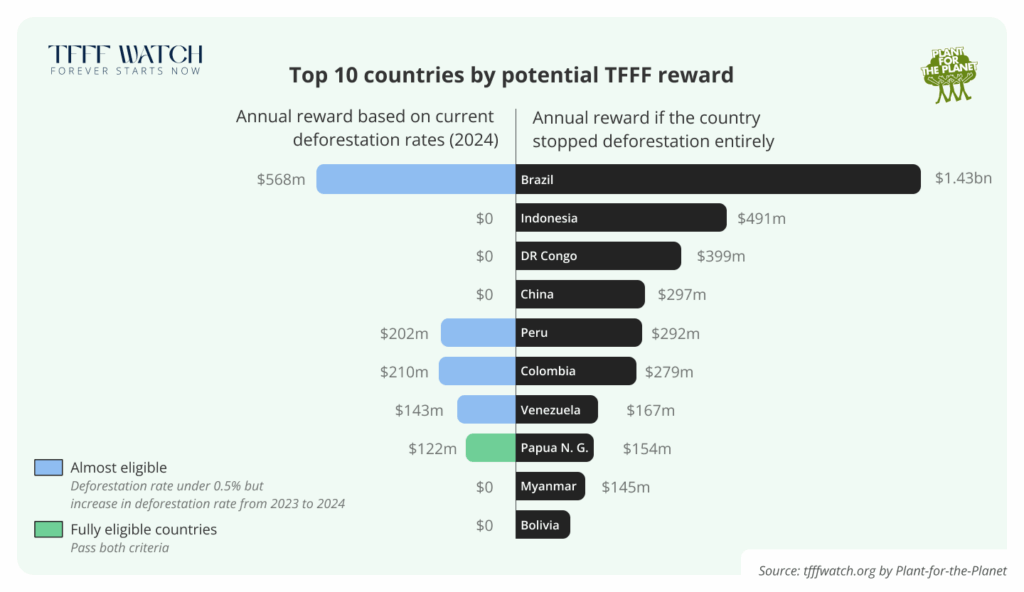

We used the TFFF methodology, outlined in Concept Note 3, and satellite data to model the potential payouts for each rainforest country. At current deforestation rates, only 20 out of the eligible 74 countries would immediately qualify for payouts (see graph below). A further 20 countries come close to being eligible.

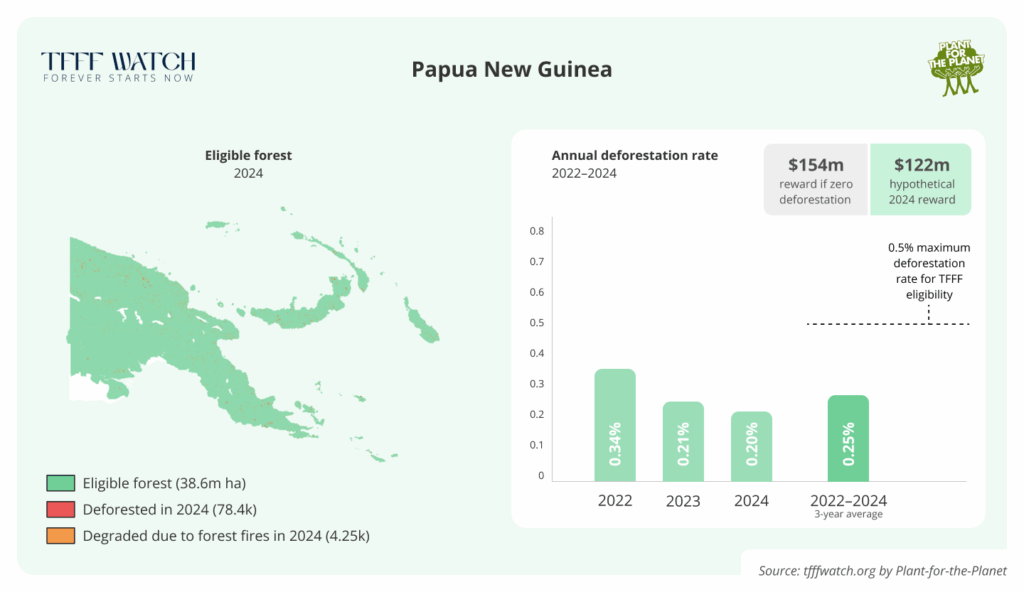

Handsome reward for Papua New Guinea

Today, Papua New Guinea has the lowest deforestation rate out of the big rainforest countries. About 80% of the island’s forest remains intact and is home to one-tenth of the world’s species. If the TFFF were already operational, the country would have received $122 million this year based on its 2024 conservation efforts. If deforestation is ended entirely, the annual reward could increase to $154 million.

Will Brazil benefit from its own invention?

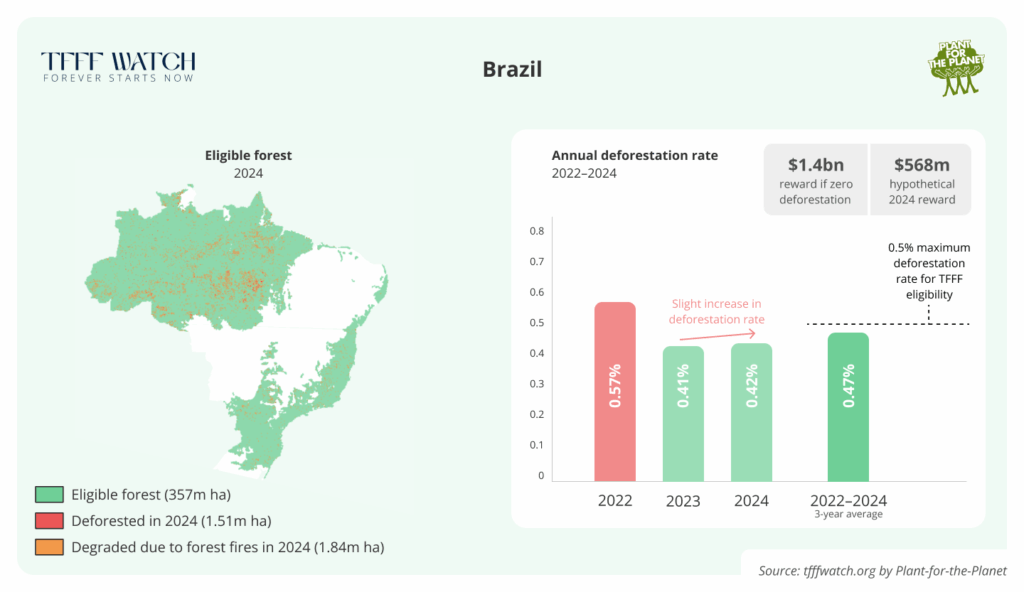

With the largest rainforest in the world, Brazil stands to benefit the most from the TFFF. If it were to end deforestation completely, it would be eligible for payouts of $1.4 billion per year. At this point, however, it wouldn’t necessarily qualify.

According to analysis from the TFFF Watch, Brazil just managed to fulfill the first requirement to join a deforestation rate below 0.5% with a rate of 0.47%. Regarding the second requirement – a declining deforestation rate – the TFFF Watch shows a slight 0.01 percentage point increase from 2023 to 2024. However, it may not even be registered using our methods of measuring deforestation, as the change is so small.

Considering the rapid decline of Brazilian deforestation rates since the beginning of Lula’s administration in 2023, it is quite likely that deforestation will once again decline in 2025, with the country becoming eligible once the TFFF becomes operational in 2026.

Since the country’s deforestation rate is still considerable, the first payout will likely be around $568 million – a bit over a third of its maximum potential.

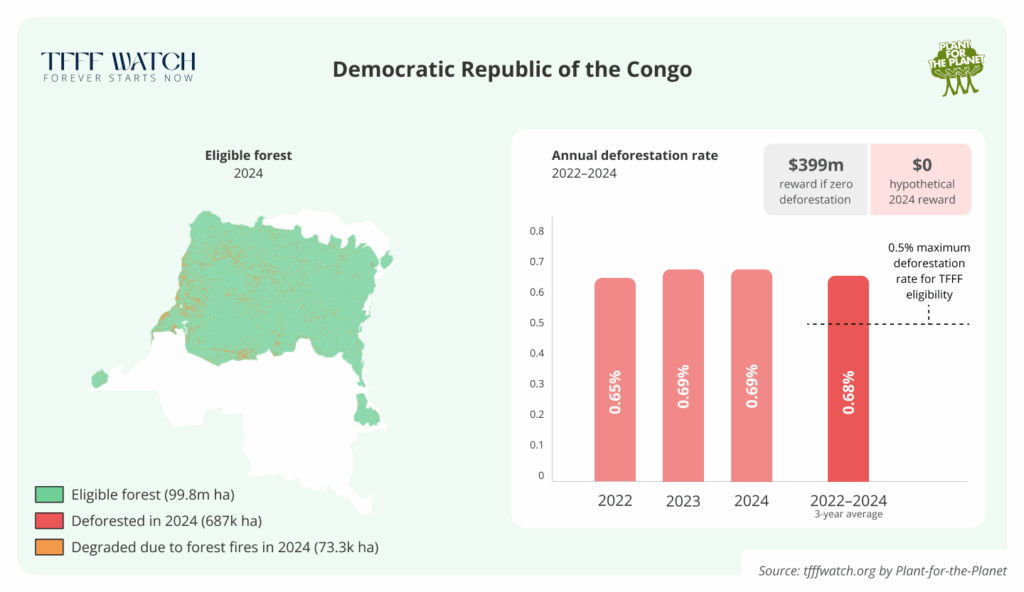

No payout for the Democratic Republic of Congo

With the third-largest tropical rainforest (99.7 million hectares eligible), the DR Congo has the potential to receive a payout of up to $399 million annually. However, its three-year average deforestation rate is above 0.5%, so the DR Congo would currently not qualify for a payout.

In 2024 alone, the DR Congo lost 0.7 million hectares of forest (0.7% of its total eligible forest), driven by shifting agriculture, wood-fuel harvesting and small-scale logging. Ongoing military conflict also makes addressing environmental degradation challenging.

The analysis makes it clear that the TFFF has enormous potential to protect rainforests. Governments must act now and follow Lula’s lead. It’s our turn to protect tropical forests – learn more at tfffwatch.org.