Planting trees is not just about the numbers 🌿

Did you know that a single tree, standing alone in the vast Sahara Desert, once served as a landmark for weary travelers navigating the endless sands? Yes, the Tree of Ténéré, dubbed “the most isolated tree on Earth,” guided generations of explorers for nearly 300 years until, in a tragic twist, it was run over by a drunk driver in 1973. Its survival sparked awe, its demise, disbelief. This acacia was the only tree within a 400km radius – in an area inhospitable to any life.

This remarkable tree’s story raises an important question: What truly defines success in tree planting? The Tree of Ténéré was iconic for its endurance in harsh, isolated conditions. So, should survival alone be the goal when planting trees? It might seem logical, but when it comes to restoring ecosystems, the picture is far more complex. In fact, some of our trees may not even survive a year.

The tree survival rates reported on our website range anywhere from 0% to 80%. A massive range, right? But here’s the twist: we plant trees not just for numbers but to restore entire ecosystems. And that requires something more valuable than survival stats – it requires biodiversity.

Sure, we could plant only the hardiest species, the ones guaranteed to survive. It would be cheaper, faster, and look great on paper. But what kind of a forest would that create? A lifeless expanse devoid of the rich interactions that define a healthy, self-sustaining environment.

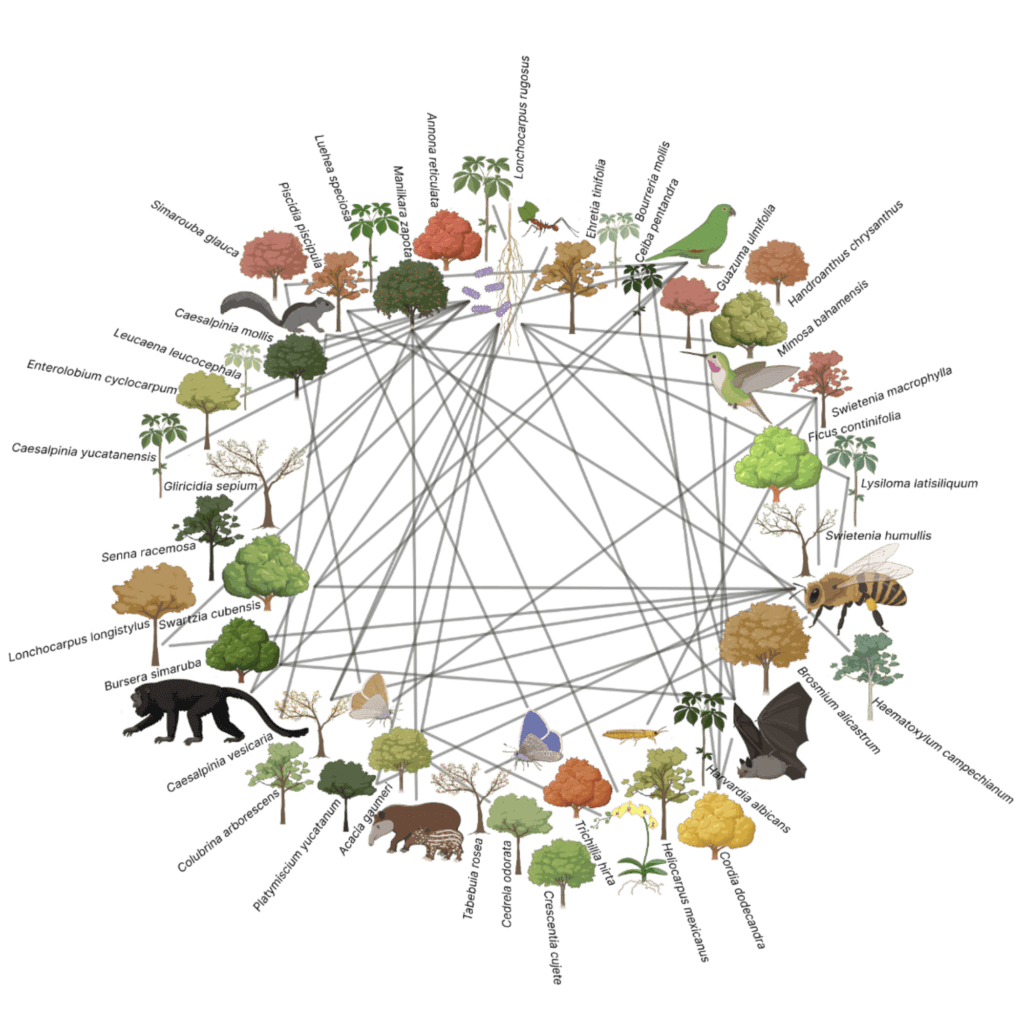

Take our Yucatán restoration site as an example. We plant over 40 species of trees there. Some flourish with survival rates of 80%, while others barely reach 10%. Why bother planting the underdogs? Because these trees serve as magnets for pollinators and seed dispersers – the unsung heroes of forest recovery. Without them, the ecosystem loses its natural momentum.

For instance, the Caesalpinia vesicaria, commonly known as Fierrillo, plays a crucial role in the ecosystem. During the dry season, it produces large inflorescences of yellow flowers that provide nectar for bees. These bees, in turn, help pollinate other plants, supporting the broader biodiversity of the forest. Even if the Fierrillo’s survival rate is low, its ecological contribution is immense.

Nature is a master of collaboration.

Every tree, every insect, every bird contributes to a complex network of life. Even a tree with a short lifespan can add nutrients to the soil, attract essential wildlife, and pave the way for stronger, more resilient growth in the future.

And it’s not just about the trees themselves. Trees create micro-habitats that provide shelter and resources for countless species. The interactions between plants, animals, fungi, and microorganisms are what make a forest more than just a collection of trees – they make it a living, breathing ecosystem.

So, when we talk about survival rates, remember: it’s not just about how many trees live today and for how long. It’s about planting the seeds of a forest that can thrive for generations and, if disaster strikes, bounce back into life without human help.

Who knows? If the Tree of Ténéré had been amongst other plant species and pollinators, perhaps, even after it was run down by a drunk driver, the tree’s offspring would still be flourishing If biodiversity had been introduced near this tree, perhaps a little oasis would have formed, becoming more than just a symbol of life – it could have been life itself.

So, let’s not get fixated on survival rates alone. Let’s plant with the planet’s long-term resilience in mind.